You are probably familiar with impedance. It is a complex number, made of the sum of a real and imaginary number. The real part is called resistance, and the imaginary part reactance.

You've probably seen some equation like this to describe the power dissipated by a current through a resistor:

$$ P = I^2 R $$

But what happens when the load can have reactance? Without going into the math, it should be obvious that if the load can be a complex number, than power can also be a complex number.

When power is represented as a complex number, it's called (uncreatively) complex power. It is the sum of active power, which is the real part, and reactive power which is the imaginary part.

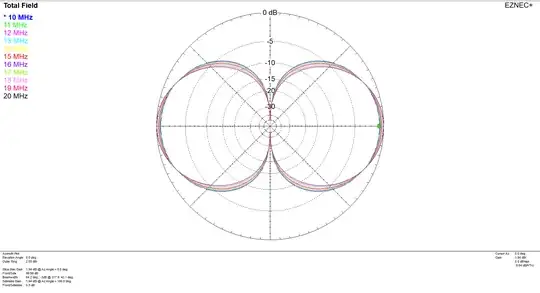

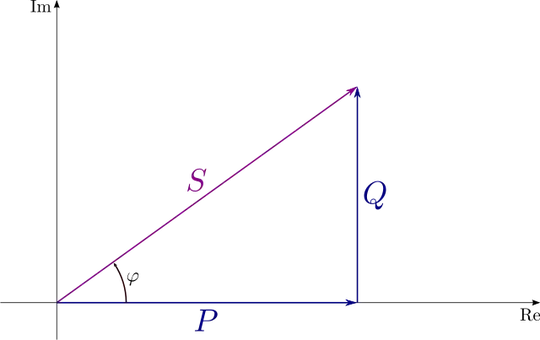

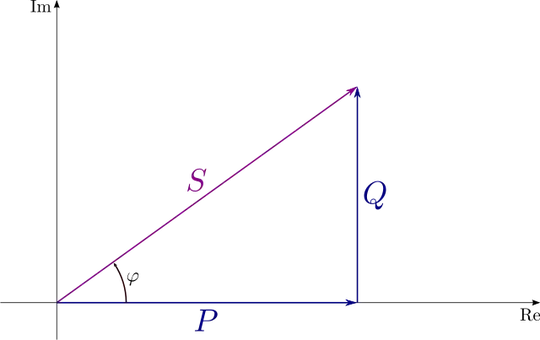

Plotting complex power on the complex plane is called the power triangle:

Eli Osherovich / CC BY-SA

$S$ is complex power, $P$ active power, and $Q$ reactive power.

As with impedance, thinking of this complex number in polar form yields some intuition. The angle to the real axis, $\varphi$, is the phase difference between current and voltage, just like impedance. And the magnitude $|S|$ is called apparent power: it's RMS voltage multiplied by RMS current.

This is all relevant because only the active power does work. One way to demonstrate this: build a circuit of any impedance with resistors, inductors, and capacitors, and apply an AC power source to it. The resistors get hot, whereas the capacitors and inductors do not (except to the extent they have non-ideal resistance).

The reactive power does no work. Consider a tank circuit of an ideal inductor and capacitor. The energy in the inductor and capacitor oscillate, but the total energy remains the same. No work is performed.

That works for ideal components, but real inductor and a real capacitor would have to be connected by a real wire. A real wire has resistance, and the wire will do work by converting electrical energy to heat according to $P = I^2 R$.

Antennas are no exception. A lot of antennas have feedlines. Feedlines have resistance. Refer to the power triangle above, and note that $|S|$ is a little bit longer than $P$. The former is proportional to the current in the feedline, whereas the latter is proportional to the work done by the antenna (radiating, if it's an efficient antenna). More reactance means higher apparent power, and thus higher current, and thus higher feedline losses for a given active power.

You asked:

Is resonance for an antenna something that should be aimed for in the interests of improved antenna performance ?

The answer, as with most engineering, is "it depends". Some people will get pedantic and argue that even if the antenna is highly reactive, it radiates just as effectively. That may be true, but a device must be usable to be performant. If the antenna is too reactive, there's simply no way to efficiently couple active power into it: all the available energy will go into overcoming losses due to the reactive power.

That said, if you look at the power triangle again, you'll notice that as long as the reactive power is small compared to the active power, $|S|$ isn't that much greater than $P$. Meaning, RMS current, and thus resistive losses, won't be substantially increased. It's certainly possible to imagine antenna designs where accepting a reasonable reactance enables an improvement in some other respect which works out to a net improvement.

It's also relevant to consider that resonance implies zero reactive power, but not necessarily a good match to the feedline. Resonance is in some cases close to the points of minimum VSWR, but that is not generally true for all possible antennas and feedlines. A VSWR above 1:1 is also associated with voltage and current in excess of the useful work performed. While any zero-reactance impedance could theoretically be matched by some feedline, such a feedline may not be practical or available. As such, it's important to not only consider reactive power, but also feedline match and the capabilities of the receiver and/or transmitter in optimizing a radio system.

Furthermore, feedline losses can largely be mitigated with the addition of a matching network at the feedpoint. The reactive power doesn't go away, but the associated increased voltage and current is then restricted to just the matching network rather than the entire feedline. If the losses in the matching network are less than they would have been in the feedline, losses can be reduced.

In addition to this, a resonant antenna apparently has the desirable effect of reducing the ratio of out of band interference to wanted signals that are within the frequency band of interest.

Yeah, somewhat. To some out of band signals, the antenna will appear reactive and thus they will experience higher loss.

But also consider many antennas that are resonant on frequency $f$ are also resonant on all odd harmonics: $3f$, $5f$, etc. At the same time, these odd harmonics are very much the ones you might want to attenuate.