Large-Scale Result

Assuming you already know the value for the current in \$R_{_\text{E}}\$ (which, by the way, you do not) and also assuming the BJTs are matched (and in a simulator they probably are) then the collector voltage difference is:

$$\begin{align*}

\Delta V_{_\text{C}}=V_{_{\text{C}_1}}-V_{_{\text{C}_2}}=I_{_{\!R_\text{E}}}\cdot R_{_\text{C}}\cdot\tanh\left(\frac{\frac12\Delta V_{_\text{B}}}{\eta\cdot V_T}\right)

\end{align*}$$

\$V_T\$ is the thermal voltage and is often taken to be about \$26\:\text{mV}\$. (However, who knows what your simulation is using?) \$\eta\$ is the emission coefficient "ideality" factor and assumed to be the same for both BJTs here. (For small signal BJTs, this is just "1". For monster BJTs like a 2N3055, it won't be 1.)

The above equation is a large-scale DC model. It will work over the entire range of the circuit. Not just small voltage differences between the bases, but large ones, as well.

The above equation, taken to its extremes, behaves as one would expect. The \$\tanh\$ function goes from -1 to +1. So when the base voltage difference reaches extremes in either direction the magnitude of resulting voltage difference cannot exceed \$\mid I_{_{\!R_\text{E}}}\cdot R_{_\text{C}}\mid\$. In short, if all of the current in \$R_{_\text{E}}\$ is directed to one BJT and not the other one, then there will be no voltage drop across one of the collector resistors and the other collector resistor will get all the current and therefore all of the voltage drop, and the difference will just be that voltage drop. This simple thought experiment verifies that the developed equation makes sense and produces the right results in the extremes.

Keeping in mind that \$\Delta V_{_\text{C}}=V_{_{\text{C}_1}}-V_{_{\text{C}_2}}\$ and \$\Delta V_{_\text{B}}=V_{_{\text{B}_1}}-V_{_{\text{B}_2}}\$, the voltage gain is:

$$\begin{align*}

A_V=\bigg| \frac{\Delta V_{_\text{C}}}{\Delta V_{_\text{B}}}\bigg|=R_{_\text{C}}\cdot\frac{\bigg|I_{_{\!R_\text{E}}}\cdot \tanh\left(\frac{\frac12\Delta V_{_\text{B}}}{\eta\cdot V_T}\right)\bigg|}{\bigg|\Delta V_{_\text{B}}\bigg|}

\end{align*}$$

How to Reach the Large-Scale Result

In perfectly matched BJTs, the collector current ratios are:

$$\frac{I_1}{I_2}\approx \exp\left(\frac{\frac12 \Delta V_{_\text{B}}}{\eta\cdot V_T}\right)$$

(This is approximate, because the Shockley equation includes a tiny -1 term in it and I've neglected it, as the other term dominates and neglecting the -1 term allows a much simpler expression to result that is a lot easier to solve and doesn't impact the result.)

Also, it's pretty obvious that the following is true due to KCL:

$$I_{_{\!R_\text{E}}}=I_1+I_2$$

This provides two equations with two unknowns, \$I_1\$ and \$I_2\$, and this can be solved and then applied to the two collector resistors to compute the difference. If you work this out on paper, you will in fact get the first equation I provided above.

Refined Large-Scale Result

There's one last detail, though: the value for \$\mid I_{_{\!R_\text{E}}}\mid\$. This will not be so simple to compute. Your approximation is obviously wrong, assuming that one of the base voltages is \$0\:\text{V}\$ and the other is \$+1\:\text{mV}\$. Clearly, the emitter voltage will be some negative value and therefore the current will be less than you propose. So the voltage gain will also be smaller than expected.

I won't show the details, but the shared emitter voltage is:

$$\begin{align*}

V_{_\text{E}}&=V_{_\text{EE}} + \eta\,V_T\:\operatorname{LambertW}\left[\frac{I_{_\text{SAT}}\:R_{_\text{E}}}{\eta\,V_T}\left(e^{^\frac{V_{_{\text{B}_1}}}{\eta\,V_T}} + e^{^\frac{V_{_{\text{B}_2}}}{\eta\,V_T}}\right)\:e^{^\frac{2\:I_{_\text{SAT}}\:R_{_\text{E}} - V_{_\text{EE}}}{\eta\,V_T}}\right]-2\:I_{_\text{SAT}}\:R_{_\text{E}}

\end{align*}$$

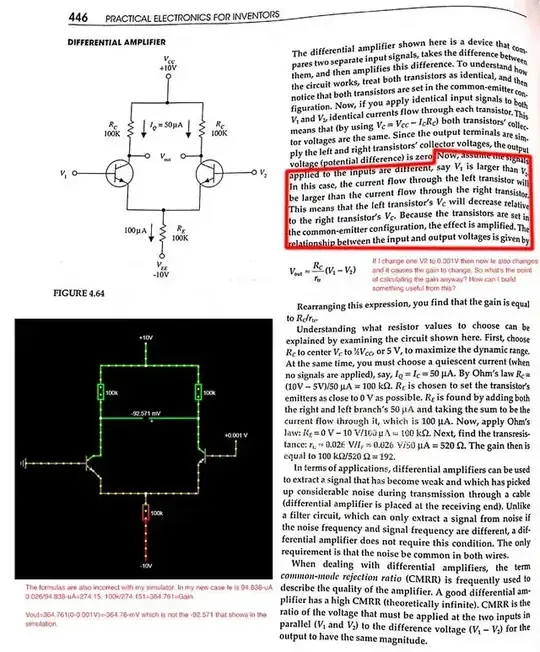

In your example circuit and using \$I_{_\text{SAT}}=1\times 10^{-14}\:\text{A}\$ and \$V_T=26\:\text{mV}\$, I get \$V_{_\text{E}}\approx -578.58\:\text{mV}\$ and therefore \$\mid I_{_{R_\text{E}}}\!\!\mid\,\approx 94.2\:\mu\text{A}\$. The estimated voltage gain is then \$\mid A_V\!\!\mid\approx 181.2\$.

Clearly, if your simulator uses different model parameters for the BJTs or if it uses a different thermal voltage, the results will likely differ. But the above is the correct approach.

Note that this is just a DC operating point solution showing how the base voltage difference affects the DC solution.

(And finally, I've ignored the difference between the emitter currents and the collector currents in the above analysis. I really should have applied \$\alpha_{_\text{F}}\$ as a factor in the first equation. But it's close to 1 and it is easy enough to adjust downward slightly the expected voltage gain.)

Small-Scale Result

If \$\Delta V_{_\text{B}}\$ is very tiny then the \$\tanh\$ function's output value is the same as its parameter value. This follows from the Taylor's expansion:

$$\tanh x = x-\frac13 x^3+\frac{2}{15}x^5-\frac{17}{315}x^7+...$$

And just selecting the first term, as the remaining terms rapidly diminish.

In this case, where the base voltage difference is sufficiently small, you can neglect the \$\tanh\$ function and get this small-difference result:

$$ A_V \approx \frac{\frac12 \mid I_{_{R_\text{E}}}\!\!\mid \cdot \,R_{_\text{C}}}{\eta\cdot V_T}$$

Taking \$\eta=1\$ (commonly done for low-power BJTs), the quiescent \$I_{_\text{E}}=\frac12 I_{_{R_\text{E}}}\$, and the small-signal BJT model value \$r_e^{\:'}=\frac{V_T}{\mid I_{_\text{E}}\mid}=\frac{V_T}{\frac12\mid I_{_{R_\text{E}}}\mid}\$, the differential gain is:

$$ A_V\approx \frac{R_{_\text{C}}}{r_e^{\:'}}$$

As \$g_m=\frac{\mid I_{_\text{C}}\mid}{V_T}\$ and \$I_{_\text{C}}\approx I_{_\text{E}}\$ it follows that \$g_m\approx \frac1{r_e^{\:'}}\$ and:

$$\begin{align*}

A_V&\approx g_m\:R_{_\text{C}}

\end{align*}$$

And in your example, this gives about the same result. So your difference is "small" enough that this DC operating point simplification is useful as an AC gain estimate.

This last equation remains approximately valid for differences up to about \$\frac12 V_T\$ (or about \$12\:\text{mV}\$), after which the gain variations are sufficient to start distorting the output signal. This means this stage, run open loop and without NFB to correct it, will distort signal inputs when the base voltage differences peak at more than a tenth of a volt.

Appendix

If you don't feel comfortable with the LambertW product-log function to form a closed solution, you can iterate to find a solution.

In this case, you can derive an iterative solution by first assuming that the collector currents and emitter currents are the same (as I have done, above), assuming we can ignore the -1 term in the Shockley equation (reasonable, too), assuming \$\eta=1\$, and then knowing that the sum of the two emitter currents must be:

$$\begin{align*}

I_{_{R_\text{E}}}=\frac{V_{_\text{E}}}{R_{_\text{E}}}&\approx I_{_\text{SAT}}\exp\left(\frac{V_{_\text{B}}-V_{_\text{E}}}{V_T}\right)+I_{_\text{SAT}}\exp\left(\frac{\left(V_{_\text{B}}+1\:\text{mV}\right)-V_{_\text{E}}}{V_T}\right)

\\\\

\frac{I_{_{R_\text{E}}}}{R_{_\text{E}}\cdot I_{_\text{SAT}}}&\approx \exp\left(\frac{V_{_\text{B}}-V_{_\text{E}}}{V_T}\right)+\exp\left(\frac{\left(V_{_\text{B}}+1\:\text{mV}\right)-V_{_\text{E}}}{V_T}\right)

\\\\&\approx\exp\left(\frac{V_{_\text{B}}-V_{_\text{E}}}{V_T}\right)\left[1+\exp\left(\frac{1\:\text{mV}}{V_T}\right)\right]

\\\\

\frac{I_{_{R_\text{E}}}}{I_{_\text{SAT}}\cdot \left[1+\exp\left(\frac{1\:\text{mV}}{V_T}\right)\right]}&\approx \exp\left(\frac{V_{_\text{B}}-V_{_\text{E}}}{V_T}\right)

\end{align*}$$

We can simplify the above by setting \$V_{_\text{B}}=0\:\text{V}\$. Then:

$$\begin{align*}

\frac{I_{_{R_\text{E}}}}{I_{_\text{SAT}}\cdot \left[1+\exp\left(\frac{1\:\text{mV}}{V_T}\right)\right]}&\approx \frac1{\exp\left(\frac{V_{_\text{E}}}{V_T}\right)}

\\\\

\exp\left(\frac{V_{_\text{E}}}{V_T}\right)&\approx \frac{I_{_\text{SAT}}\cdot \left[1+\exp\left(\frac{1\:\text{mV}}{V_T}\right)\right]}{I_{_{R_\text{E}}}}

\\\\

\frac{V_{_\text{E}}}{V_T}&\approx \ln\left(\frac{I_{_\text{SAT}}\cdot \left[1+\exp\left(\frac{1\:\text{mV}}{V_T}\right)\right]}{I_{_{R_\text{E}}}}\right)

\\\\

V_{_\text{E}}&\approx V_T\cdot \ln\left(\frac{I_{_\text{SAT}}\cdot \left[1+\exp\left(\frac{1\:\text{mV}}{V_T}\right)\right]}{I_{_{R_\text{E}}}}\right)

\end{align*}$$

Let's assume \$I_{_{R_\text{E}}}=100\:\mu\text{A}\$ to start, that \$I_{_\text{SAT}}=1\times 10^{-14}\:\text{A}\$, and that \$V_t=26\:\text{mV}\$. Then we'd find at the first iteration that \$V_{_\text{E}}\approx -580.1\:\text{mV}\$. From this, we can work out that \$I_{_{R_\text{E}}}=\frac{-580.1\:\text{mV}-\left(-10\:\text{V}\right)}{100\:\text{k}\Omega}\approx 94.2\:\mu\text{A}\$. Re-computing, find \$V_{_\text{E}}\approx -578.59\:\text{mV}\$. From this, find \$I_{_{R_\text{E}}}=\frac{-578.59\:\text{mV}-\left(-10\:\text{V}\right)}{100\:\text{k}\Omega}\approx 94.2\:\mu\text{A}\$, again. So we are done with iterations. And you can see that this value, \$V_{_\text{E}}\approx -578.59\:\text{mV}\$, is very close to the value computed using the LambertW function, above.