I guess Captain Man hasn't found any of the explanations satisfactory yet.

So to your first contention, Captain Man:

All antennas are a compromise.

No, not if they are purpose built.

Are there any antennas that in free space perform strictly worse than an isotropic antenna would?

That depends on what you mean by worse in your application. I would say an isotropic antenna is the worst in all cases because I'm not trying to place radio energy in all directions, I want it in certain directions, to the detriment of other directions.

Or a simple flat ground model?

If you're talking about a ground plane antenna, I consider these almost as bad as a theoretical isotropic antenna due to ground losses.

I've seen all the articles about best lengths for random wire antennas. At some point, it occurred to me that while these may have a reasonable SWR that can be tuned on most bands,...

These "best lengths" are usually because someone has worked out how to get a particular length of antenna to be within the tuning range of either a radio's built-in tuner if it has one, or an external tuner, since by design, tuners can only tune-out a certain amount of mis-match.

... it doesn't necessarily mean they've got good gain.

Gain is relative, and affected by several items, first, the antenna's proximity to ground, because the the Earth can be a reflector and an absorber of energy, and to the extent it acts as a reflector, your pattern is impacted by the extent of the reflections are in or out of phase with the currents on your antenna.

Watch this video of an antenna in free space, as the number of wave lengths on it increases, and see how it's pattern changes.

Varying Antenna Lengths in Free Space

You'll notice lobes are created that will have very high gain in those particular directions, and conversely, deep nulls in other directions. Now, keep in mind this is a free space model, here on Earth, your lobes and nulls will be much more of a compromise, and as in one of my antenna designs, even my null has about 7dBi gain, while my main lobes have 12dBi gain...not a bad compromise; what I did sacrifice was sending energy straight up into the sky, but that is where it is useless to me.

Remember, your particular antenna performance in any given band is going to be affected by how many wave lengths long it is on that band, it's height above ground at every point on the antenna (I'm looking at you slopers), the characteristics of your Earth at your location, and it's overall design.

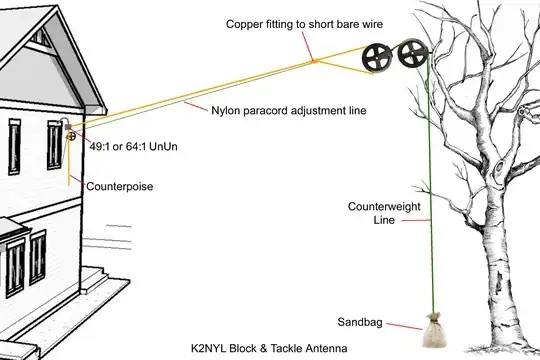

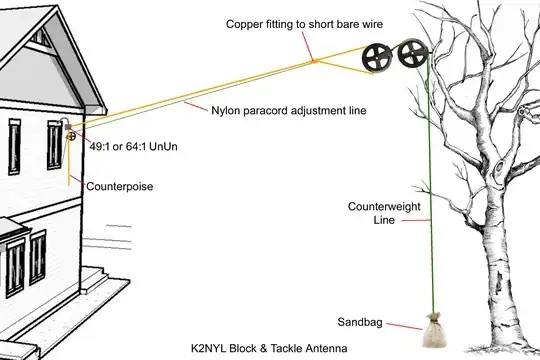

Here's a tunable end-fed antenna that will work multi-band without a tuner with a 49:1 or better yet, a 64:1 UnUn.

You need to make provision to have your counterpoise wire, be easily changeable or adjustable to get the widest range of bands; the lengths will be determined by experimenting with pulling the main radiating element in and out, adjusting for the lowest SWR in the middle of a given band, and then cutting back, or otherwise changing the length of the counterpoise to get to the lowest possible SWR; you may also find you are still adjusting the main radiator at the same time as you are moving your voltage feed-point every time you adjust the length of either element. Your antenna's lowest band will be where your main radiating element is a little less than a half wavelength in length of a given band. I can get 1.6:1 SWR on 80M, on my vertical 40M antenna, by lengthening the main radiator from ~65' to ~67', but that's where I run out of wire. To make this design adjustable, you need flat-strap braided copper; 3/16" is strong enough for an 80M design, or 1/4" is strong enough for a 160M antenna (~75M in length). This design makes a "random" antenna, much less random, because you can tune it without a tuner, and you can tune-out the random environmental effects of your particular location/situation. There's plenty written about end-fed halfwave antennas, so I'm not going to go into the design elements here, I'll only say that your counterpoise is typically about 0.05 of a wavelength for the band you want it to work on; with that said, my 40M counterpoise works just as well well on 20M and fairly well on 15M, but needs adjustment on 17M, 12M & 10M. Also remember, you don't have to shorten the main radiator of the antenna to 5M to use it on 10M, you just need to tune it a little so that it's resonant, and that may be three feet, in one direction or another, as compared with your overall length. You will have multiple current loops on the antenna, and that will give directionality to it, but that could be highly desirable if you orient the antenna in a way where those lobes are in a direction you find useful.

You need to make provision to have your counterpoise wire, be easily changeable or adjustable to get the widest range of bands; the lengths will be determined by experimenting with pulling the main radiating element in and out, adjusting for the lowest SWR in the middle of a given band, and then cutting back, or otherwise changing the length of the counterpoise to get to the lowest possible SWR; you may also find you are still adjusting the main radiator at the same time as you are moving your voltage feed-point every time you adjust the length of either element. Your antenna's lowest band will be where your main radiating element is a little less than a half wavelength in length of a given band. I can get 1.6:1 SWR on 80M, on my vertical 40M antenna, by lengthening the main radiator from ~65' to ~67', but that's where I run out of wire. To make this design adjustable, you need flat-strap braided copper; 3/16" is strong enough for an 80M design, or 1/4" is strong enough for a 160M antenna (~75M in length). This design makes a "random" antenna, much less random, because you can tune it without a tuner, and you can tune-out the random environmental effects of your particular location/situation. There's plenty written about end-fed halfwave antennas, so I'm not going to go into the design elements here, I'll only say that your counterpoise is typically about 0.05 of a wavelength for the band you want it to work on; with that said, my 40M counterpoise works just as well well on 20M and fairly well on 15M, but needs adjustment on 17M, 12M & 10M. Also remember, you don't have to shorten the main radiator of the antenna to 5M to use it on 10M, you just need to tune it a little so that it's resonant, and that may be three feet, in one direction or another, as compared with your overall length. You will have multiple current loops on the antenna, and that will give directionality to it, but that could be highly desirable if you orient the antenna in a way where those lobes are in a direction you find useful.

And keep experimenting with antenna software, it is a very useful modeling tool for patterns and understanding feed-point impedances for various designs. EZ-NEC 7 is free and has many sample antenna designs that you can modify and play around with until you get the hang of it.