EDIT: Simple answer to the new edited question

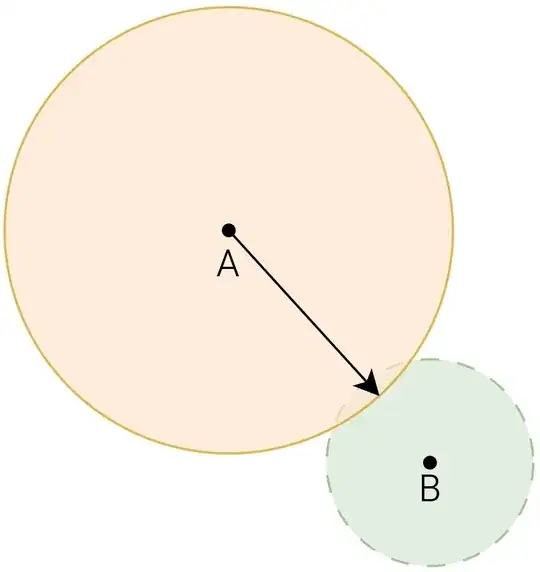

The answer is no. Those orange and green circles are a highly abstract representation, but real radio communication doesn't work that way.

Let's use a greatly simplified analogy. Two people are trying to talk, say, in the middle of an empty field or somewhere. Person A is speaking, Person B is listening. How far apart can they be and still be able to communicate? That depends on how loud A is, which direction A turns to, how good the hearing B is, and how much ambient noise there is. If there is greater attenuation between them (fresh snow, vegetation, etc.), that further reduces the communication range.

You cannot define the "speaking range" of A or the "hearing range" of B in isolation. Communication range is determined by considering both simultaneously, along with the ambient noise at the site of B.

My earlier answer, below, describes the same principle, but using the radio terminology.

The Elusive Metric of Communication Range

Communication range is a broad and approximate metric that should not be taken literally. To accurately determine communication range, it's essential to clearly define assumptions and conditions, using either empirical measurements or theoretical calculations as the framework. Without this clarity, the range becomes a rule of thumb with many unknowns and implicit assumptions.

Factors Affecting Communication Range

Transmitter Side

On the transmitter side, several factors influence communication range:

- Antenna Radiation Pattern: The directionality and efficiency of the antenna.

- Transmission Power: The amount of power used to transmit the signal.

- Height: The elevation of the transmitting antenna.

Propagation Path

- Obstacles: Terrain, buildings and other structures would attenuate the direct wave (VHF and higher) or ground wave (lower VHF and HF). LF may propagate around the obstacles to some extent, depending on the dimensions.

- Moisture: In upper UHF to lower SHF, moisture may absorb significant signal power, leading to additional attenuation. In higher SHF, moisture may reflect the signal power.

There are other factors that influence the propagation attenuation in addition to the dilution of the power density in free space.

Receiver Side

On the receiving side, various factors come into play:

Antenna Radiation Pattern: Similar to the transmitter, the receiver's antenna pattern affects how well it can pick up signals and the environmental noise.

Height: The elevation of the receiving antenna.

Environmental Noise: This includes noise from space, atmospheric sources, terrestrial activities (both natural and man-made).

Receiver Noise: The receiver also generates noise within it.

Signal to Noise Ratio

The received signal power is a tiny fraction of the transmitter signal picked up by the receiver antenna. However, this signal must compete with various noise sources:

- Space Noise: Background radiation from outer space.

- Atmospheric Noise: Interference from atmospheric conditions.

- Terrestrial Noise: Man-made and natural noises on Earth.

- Receiver-Generated Noise: Internal noise produced by the receiver's electronics.

The total noise power is the sum of these sources. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) within a specific bandwidth determines whether communication is feasible. This bandwidth can vary:

- FM: Approximately 15 kilohertz.

- Single Sideband (SSB): Around 3 kilohertz.

- Morse Code (CW): Just a couple of hundred hertz.

Keep in mind that, in most situations, the noise is uniformly distributed whereas the signal spectrum is concentrated in those bandwidths, so adjusting the receiver's filter bandwidth according to the modulation scheme would maximize the SNR (and range). I don't like the terminology, but it is often called "Wiener gain" or "magnitude-only Wiener filter." Those terms are commonly used by the speech and psychoacoustic research community (which I used to be a part of) but probably never considered appropriate by the signal processing research community (which I am also a part of).

In terms of how the transmitter, propagation path and receiver arrangement as a whole will determine the communication feasibility and the system performance, you might want to look up "link budget equation" and "Friis equation." (Those are in any radio propagation textbook but Wikipedia is also fine. ChatGPT can teach you on these topics as well.)

Practical Considerations

Lower Frequencies (HF and Below)

At lower frequencies, the noise picked up by the receiver antenna is high. Modern receivers are generally sensitive enough that additional gain does not improve performance. The key factors here are:

- Noise Immunity: The receiver's ability to mitigate the noise (mostly antenna's directivity and polarization).

- Interference Immunity: The receiver's resistance to interference from other signals (both in-band and out-of-band).

Higher Frequencies (Upper VHF and Above)

At higher frequencies, unless the environment is very noisy, it's easier to avoid excessive noise coming from the antenna. In this case, the limiting factors are:

- Receiver Gain: The amplification capability of the receiver.

- Receiver Noise: Internal noise generated by the receiver.

In RF engineering, two critical terms often come up:

- Sensitivity: The minimum signal strength required for the receiver to produce a usable output.

- Noise Figure: A measure of the degradation of the SNR caused by components in the radio frequency (RF) signal chain.

At lower frequencies like HF, sensitivity and noise figure can be measured but are often not performance limiting factors. The real challenges lie in noise and interference immunity. At higher frequencies, receiver gain and internal noise become directly relevant because interference and environmental noise are relatively easier to avoid and less relevant. Thus, the receiver performance is discussed in different metrics depending on the frequency.

Conclusion

There is no single metric for communication range because it depends on numerous variables.