The design guide assumes cylindrical conductors. I'm stuck with rectangles; am I fairly safe if I just say one dimension equates to the diameter and ignore the other (which is set by PCB thickness)?

no, I don't think so. If anything, assume the smaller dimension is the limiting one, and the the width of the other was chosen larger to compensate for effects like vias not actually forming a connection in the direction that current needs to flow.

But this is just guesswork; analytic formulas won't represent that, so you need to simulate, then measure the real properties of your board and of a "pseudo-cylindric dipole" formed with traces and vias, and adjust the simulation till you can predict reality.

If I make the conductors square in cross section, I need to adjust the conductor lengths. The guide has graphs for that but I want a formula. Anyone know where I can find it? The guide cites Viezbicke, who doesn't have the formulas, and I'd rather not dig through his sources

No such formula exists to the best of my knowledge. To be honest, I don't think it's a wise idea to have a central conductor in a Yagi design when you don't need it for mechanical stability and the elements are this wide compared to their spacing. I might be wrong, the shape you show might be a result from a whole series of experiments and simulations.

If that is true for the general shape, then it's also true for the distances.

Is there any good way to set the driven element length besides taking the average of reflector and 1st director length?

that wouldn't be right even for an idealized "infinitesimally thin" conductor Yagi-Uda. That stuff actually comes from a paper with formulas, and there's theoretical optima.

For round non-infinitesimally thin conductors there's approximate formulas, that work well in practice.

However, in this situation where shapes are so far from ideal, you'll simulate. And then adjust the model you're simulating, until you get something that works well.

So, all your questions sadly are answered with

You build a simulation, and then optimize the antenna you simulate until it works well.

You then order a prototype, measure, and if necessary, improve your simulation and re-optimize.

It is a very human trait to hope for a simple formula to design a complex system, but the truth is that complex antennas are based on one fundamental, "easy" set of equations (Maxwell's), and anything that describes an antenna is build atop of these. If the resulting formula is easy, then only because specific properties of the antenna simplified the complexity of applying Maxwell to every point in and around the antenna (there's uncountably infinitely many of these), and looking at the resulting system of differential equations. We can model a Hertian dipole easily with a single formula, because we assume simplifying assumptions, we can model a simple thin dipole in vacuum with a formula, we are somewhat mediocre at describing thick dipoles in vacuum, and real dipoles on real masts interacting with real environments: we use very approximate formulas and use a lot of safety margin to account for "… and then reality happened".

That doesn't work as soon as things become complicated enough. We then fall back at taking our antennas, picking them into parts that are small enough that we can model them as "simple" elements, and do the formulas on each part individually, then combine what happened to each part individually with its neighbors, do the same thing as before, but under the new conditions, and repeat. That is exactly what an electromagnetic field simulation does.

So, really, yeah, you will need to simulate.

And the fact that you're using a low-cost PCB boardhouse won't make that easier: you get cheap PCB substrate (which will probably be fine for your use case, don't you worry too much!), which will have only loosely defined electromagnetic properties. So, first step would be to actually measure the loss angle and permittivity of your PCB material! People typically do that with a simple coplanar waveguide (or some other simple geometry), because, recognizing a pattern here, for very simple things, you have formulas that tell you what you should be observing given an $\epsilon_r$, so if you measure something, you can then draw conclusions on the unknown $\epsilon_r$.

Atfer you've characterized your board material, you'd probably go ahead and build a script that outputs a PCB layout for an antenna, based on adjustable parameters (such as "length of driven element", "length of reflector" "widths of each element", "spacing of directors", "length of first director", "coefficient of exponential reduction of director length with distance from driven element" or such). You feed it with an initial set of assumed values, generate the PCB layout, throw that into your EM solver, and calculate one "badness" $b$ value (in our example, the inverse of gain in the desired direction would be a good choice, but you might add badness points for overall length, or set badness very high when "forbidden" things, like directors touching each other, happen).

So now you have a combined functionality that gives you

$$ \text{parameter set }\quad \mathbf v \mapsto b,$$

so you can directly ask your computer "when I twiddle a bit on this one or two parameters, how much better or worse does my antenna get?".

Then, you just let your computer do the asking of questions. You start with your initial parameter set $\mathbf v_{\text{initial}}$, and tell python, octave, CST studio etc to optimize. They will do that by adjusting the parameters, and looking whether badness went up or down. It will then automatically pick values that will allow it to test which parameters need to be increased, which decreased, to become better. As long as your problem is mostly convex, meaning that your initial guess is generally right, and there's an uninterruptedly downhill slope from your initial guess to the best possible antenna, it's likely your computer would find it.

So, how to do that, practically: I can think of two EM solvers in the realm of free and open source software, OpenEMS and Elmer, of which Elmer is certainly the more general-scope simulation software (it's not only an electromagnetic solver, but also a solid mechanic/acoustic/fluid dynamics/heat dissipation/particle simulator), and OpenEMS is the more classical one with more antenna examples. In the world of paid software, CST Studio is what you'd typically use, and it's way more polished to antenna designer and electronics simulators. It's also way more expensive than I want to afford (there's a free "learning" version, but guess what, it disables antenna optimization routines, because that's what enables users to earn a lot of money by using that software).

Because it got mentioned in the comments: NEC (i.e., NEC-2 derivatives like xnec, necpp) will not suffice as simulator (how a 1981 very limited-use case wire antenna simulation program has this high popularity in 2024 is a bit beyond me). It makes simplifying assumptions that don't hold: NEC is for infinitely thin wire antennas only, and using approximate extensions, for "perfectly tubular" wires. It can somewhat well do a "classical" wire Yagi, it defintely can't do antennas where the conductors aren't "generally wire-shaped". And the whole point of your exercise is that your antenna is not sufficiently modeled as wires.

So, I'd probably start out with OpenEMS' python interface, wade through a few of their tutorials (which might be written in octave script rather than Python, and if you prefer matlab/octave rather than python, then stick with that), then verify I can optimize the length of a thin dipole for a given wavelength, then verify I can optimize a thick dipole, then optimize a flat (rectangular) dipole, then move on to a dipole with a reflector, and then start adding director elements. If all this works flat, I'd look into extending into the next dimension, by adding a slate of specified-$\epsilon_r$ material under the conductors.

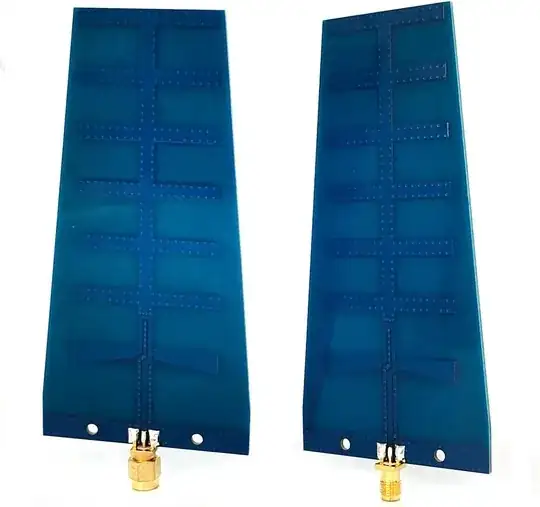

on Amazon. I thought, "how hard could it be to make a crappy 5.2GHz antenna I can have OshPark print for a couple bucks?" Turns out it's harder than I thought.

on Amazon. I thought, "how hard could it be to make a crappy 5.2GHz antenna I can have OshPark print for a couple bucks?" Turns out it's harder than I thought.