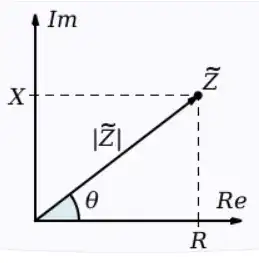

Impedance is the sum of resistance and reactance:

$$ Z = R + jX $$

$j$ is the imaginary unit, equal to $\sqrt{-1}$. Some equations use $i$ instead to mean the same thing.

Reactance is a concept that describes the effects of capacitors and inductors, as well as other components that introduce a phase shift between voltage and current, but don't dissipate energy.

For example, the reactance of a capacitor is given by:

$$ X_C = {-1 \over 2 \pi fC} \tag 1 $$

And for an inductor:

$$ X_L = 2 \pi fL \tag 2 $$

where $C$ is capacitance (farads), $L$ is inductance (henrys), and $f$ is frequency (hertz). From this you can see for capacitors and inductors (and in practice, most other things) the reactance depends on frequency, and capacitors have negative reactance whereas inductors have positive reactance.

The unit of impedance, resistance, and reactance is ohms in each case. Impedance is represented by a complex number, but the unit is still ohms.

That's the theory.

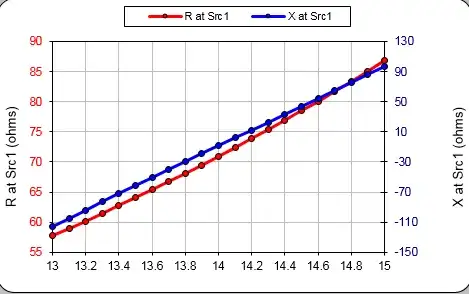

In practice, you won't be able to measure the impedance of your antenna with an LCR meter. As you can see in equations 1 and 2, reactance (and thus impedance) depends on frequency. The LCR meter works by measuring the impedance at some frequency, then working backwards though equations 1 or 2 to find the inductance or capacitance.

This works OK for inductors and capacitors (at least, when operating at frequencies where parasitic effects are negligible), but an antenna is something else so equations 1 and 2 don't apply.

Instead, people use an antenna analyzer to measure the impedance directly at the frequency where the antenna is intended to be used.

If you don't have an antenna analyzer, you can use an SWR bridge. This will tell you how close you are to 50 ohms, though not in what direction. There will be a dip in SWR around where the antenna is resonant. Making the antenna longer moves this dip lower in frequency, and making the antenna shorter moves it higher. By measuring SWR at several frequencies and iteratively adjusting the length of the antenna, it's possible to get the antenna to be the right length for the desired frequency.